CNN

—

Scientists using ice-breaking ships and underwater robots have found that Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier is melting rapidly and may be on an irreversible path to collapse, a catastrophic global sea-level rise.

Since 2018, a team of scientists making up the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration has been studying Thwaites – often called the “doomsday glacier” – to better understand how and when it will collapse.

Their findings, set in a suite of studies, provide a clearer picture of this complex, ever-changing glacier. The outlook is “grim,” the scientists said in a report released Thursday, which reveals the main results of their six-year research.

They found that rapid ice loss could accelerate this century. The retreat of the Thwaites has accelerated significantly over the past 30 years, said Rob Larder, a marine geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey and one of the ITGC team. “Our findings are set to recede more and more rapidly,” he said.

Scientists predict the Thwaites and Antarctic ice sheets will collapse within 200 years, with catastrophic consequences.

The Thwaites hold enough water to raise sea level by more than 2 feet. But it acts like a cork, holding back the vast Antarctic ice sheet, whose collapse could eventually lead to about 10 feet of sea-level rise, devastating coastal communities from Miami and London to Bangladesh and the Pacific islands.

Scientists have long known that Florida-sized thwaites are vulnerable, in part because of its geography. The land it sits on is sliding downward, meaning that as it melts, more ice is exposed to relatively warm ocean water.

Yet relatively little is understood about the mechanisms behind its retreat. “Antarctica is the biggest wild card for understanding and predicting future sea-level rise,” ITGC scientists said in a statement.

Over the past six years, a range of experiments by scientists have sought to bring more clarity.

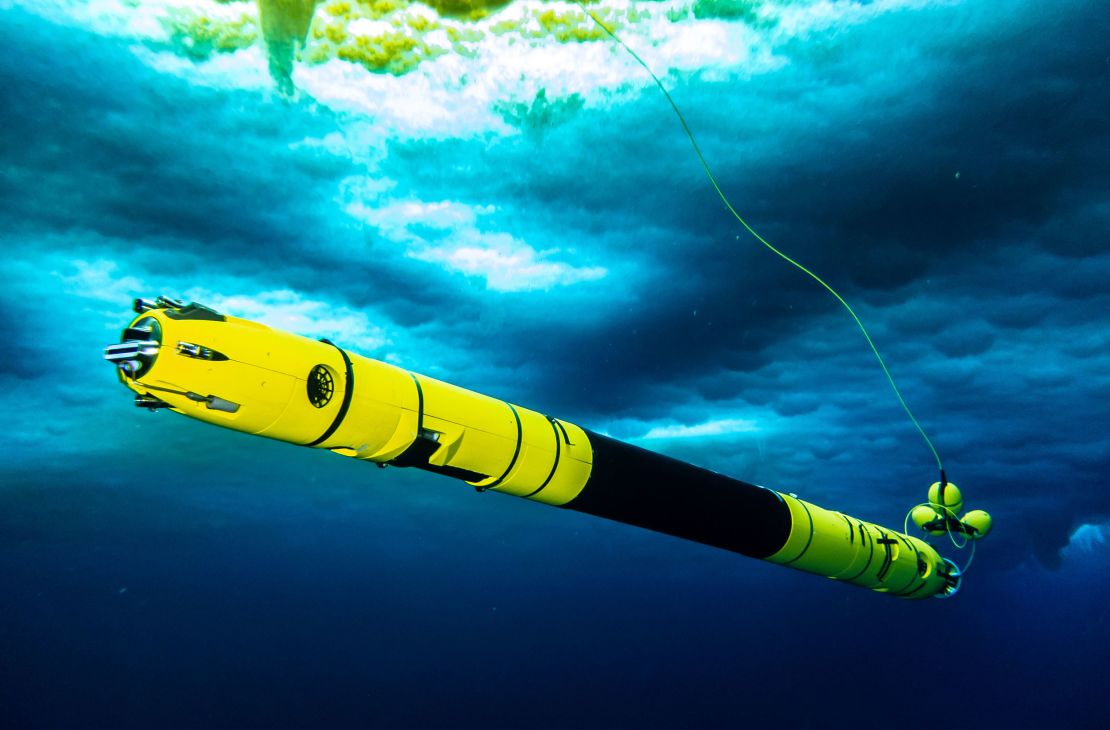

They sent a torpedo-shaped robot called the IceFin to the ground line of the Thwaites, where the ice rises from the seabed and begins to float, the critical point of impact.

Gia Riverman, a glaciologist at the University of Portland, said the first clip of the iceberg swimming to the ground was emotional. “For glaciologists, I think it had the emotional impact that the moon landing had on the rest of society,” he said at a new conference. “It’s a big deal. We’re seeing this place for the first time.

Through backlit images of the icefin, they discovered that the glacier is melting in unexpected ways, with warm ocean water funneling through deep cracks and “staircase” formations in the ice sheet.

Another study used satellite and GPS data to look at the effects of the waves and found that seawater pushed more than 6 miles beneath the Thwaites, forcing warmer water under the ice sheet and causing it to melt faster.

Even more scientists have investigated the history of Thwaites. A team including Julia Wellner, a professor at the University of Houston, analyzed marine sediment cores to reconstruct the ice sheet’s past and its rapid retreat in the 1940s, likely triggered by a very strong El Niño event — a natural climate fluctuation. There is a warming effect.

The results “add more detail than is available by looking at modern ice and teach us a lot about ice behavior,” Wellner told CNN.

In the dark, there was also some good news about a process scientists fear could cause rapid melting.

There are concerns that if the Thwaites’ ice shelves collapse, it could expose towering glaciers to the sea. These tall cliffs can easily become unstable and fall into the sea, revealing even taller cliffs behind them, and the process repeats itself.

However, computer modeling has shown that this phenomenon is real, and the chances of it happening are less than previously feared.

That’s not to say Thwaites is safe.

Scientists predict that the entire Thwaites and the Antarctic ice sheet behind it could be gone by the 23rd century. Even if humans stop burning fossil fuels quickly—which they haven’t—it may be too late to save.

While this phase of the ITGC project is coming to an end, scientists say more research is needed to find this complex glacier and understand whether its retreat is now irreversible.

“Despite progress, we still have deep uncertainty about the future,” said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine and part of the ITGC. “I’m very concerned that this part of Antarctica is already in decline.”