WASHINGTON, May 22 (Reuters) – President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy met at the White House on Monday to discuss raising the U.S. government’s $31.4 trillion debt ceiling.

The Democratic leader and top congressional Republicans struggled to make progress on a deal as McCarthy pressed the White House to agree to spending cuts in the federal budget that Biden called “drastic.”

They have just 10 days – until June 1 – to reach an agreement to raise the government’s self-borrowing limit or trigger unprecedented debt repayments that economists say could bring on a recession.

Biden told reporters as the meeting began that he was “hopeful” they could make some progress. He said a bipartisan agreement is needed for both parties to “sell” to their constituencies, and there may still be some disagreements.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on Monday offered a sobering reminder of how little time remains, saying the previous estimated default date was June 1 and that it was “highly likely” the Treasury would not be able to pay off all government obligations by early June. The debt ceiling has not been raised.

White House aides met with Republican negotiators on Capitol Hill for two hours on Monday, and early indications are that talks went well.

“I’m confident that what we’re negotiating now, the majority of Republicans will see as the right place to get us on the right track,” McCarthy told reporters.

Any deal to raise the cap would have to pass both houses of Congress and would therefore depend on bipartisan support. McCarthy’s Republicans control the House 222-213, while Biden’s Democrats hold the Senate 51-49.

Failure to raise the debt ceiling could roil financial markets and trigger defaults that would raise interest rates on everything from car payments to credit cards.

US markets rose on Monday as investors awaited updates on the talks.

If Biden and McCarthy come to an agreement, it will take several days to push the legislation through Congress. McCarthy said a deal must be reached this week to pass Congress and be signed into law by Biden to avoid default.

A White House official on Monday said Republican negotiators last week proposed additional cuts to programs that provide food assistance to low-income Americans, and stressed that no deal could pass Congress without bipartisan support.

Cuts and clawbacks

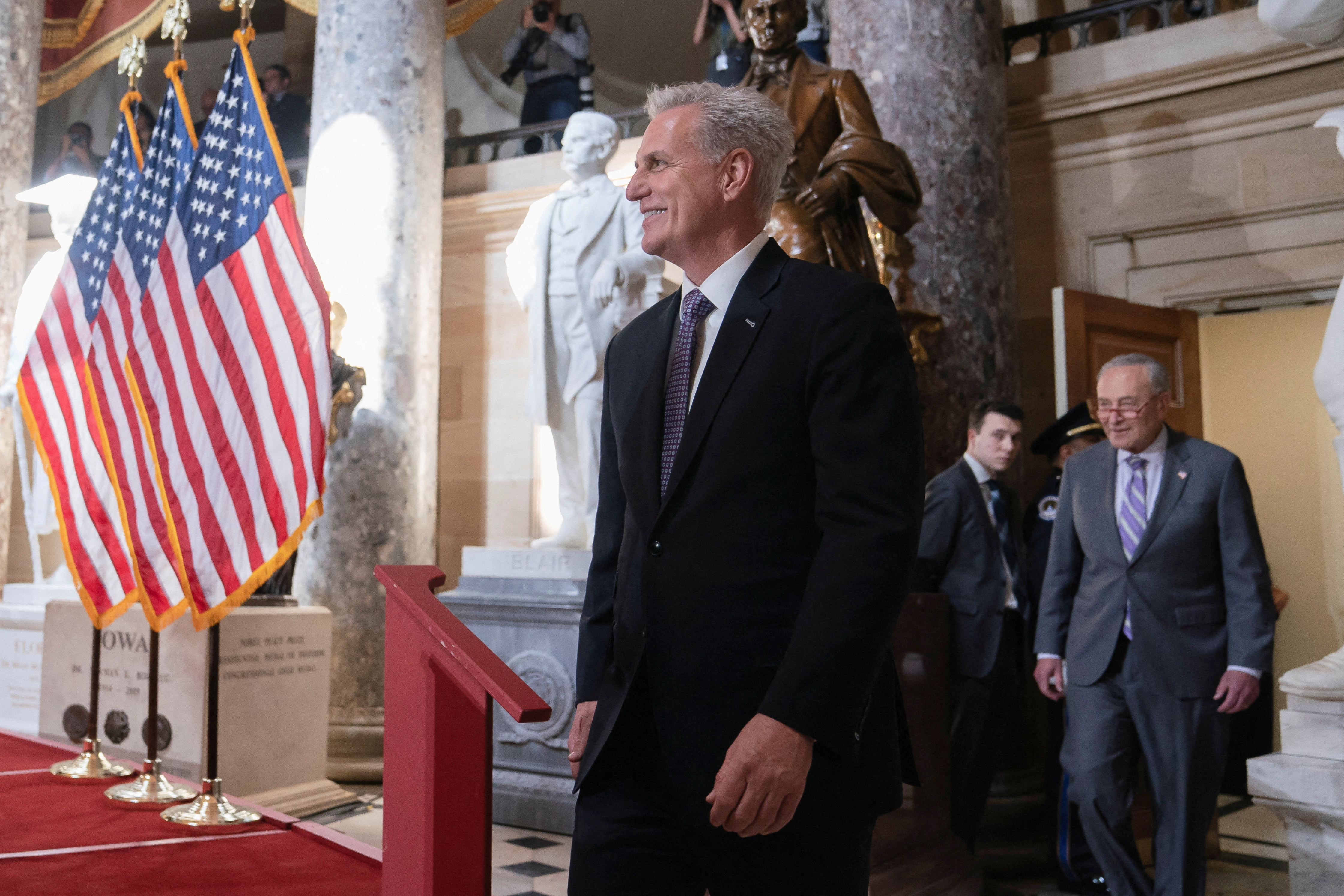

[1/2] House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) arrives for the unveiling of a portrait of former Speaker Paul Ryan on Capitol Hill on May 17, 2023 in Washington, U.S. REUTERS/Nathan Howard/

Republicans favored discretionary spending cuts, new work requirements for some programs for low-income Americans and a clawback of COVID-19 aid approved by Congress but not yet spent in exchange for a debt ceiling increase to cover lawmakers’ costs. Previously approved spending and tax deductions.

Democrats want to keep spending steady at this year’s levels, while Republicans want to return to 2022 levels. A plan passed by the House last month would cut government spending by 8% next year.

Biden, who has made the economy a centerpiece of his domestic agenda and is running for re-election, has said he would consider spending cuts along with tax changes, but called the Republicans’ latest offer “unacceptable.”

The president tweeted that he would not support “Big Oil” subsidies and “rich tax cheats” while jeopardizing health and food assistance for millions of Americans.

Both sides must weigh any concessions against pressure from hard-line factions within their own parties.

Some members of the far-right House Freedom Caucus insisted on halting the talks, demanding that the Senate take up their House-passed legislation, which was rejected by Democrats.

McCarthy, who made extensive concessions to right-wing hardliners to win the speakership, risks being fired by members of his own party if he doesn’t like the cut deal. After losing the 2020 election to Biden, former Republican President Donald Trump has urged members of his party to minimize any economic consequences and force default if all of their goals are not met.

Liberal Democrats have pushed back against any cuts that would harm families and low-income Americans, with some urging Biden to act on his own by invoking the Constitution’s 14th Amendment — something the president said Sunday would face sanctions.

The amendment states that “the validity of the public debt of the United States … shall not be questioned,” but this provision has often been overlooked by courts.

Biden is looking for a solution after months of refusing to negotiate on the debt ceiling, insisting that Republicans must pass a “clean” unconditional increase before agreeing to any spending talks.

In Japan on Sunday, he acknowledged the political implications, saying some far-right House Republicans “know the damage it will do to the economy.” – Selection.

Congress has raised the debt ceiling three times under Trump, without demands from Republicans for sharper spending cuts.

Reporting by David Morgan, Richard Cowan and Andrea Shalal; Written by Susan Hevey; Editing by Lisa Shumaker and Stephen Coates

Our Standards: Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.